Opinion on the future of cryptocurrency remains divided and dogmatic. The protagonists see it transforming the global payments system. The sceptics see it as a solution in search of a problem.

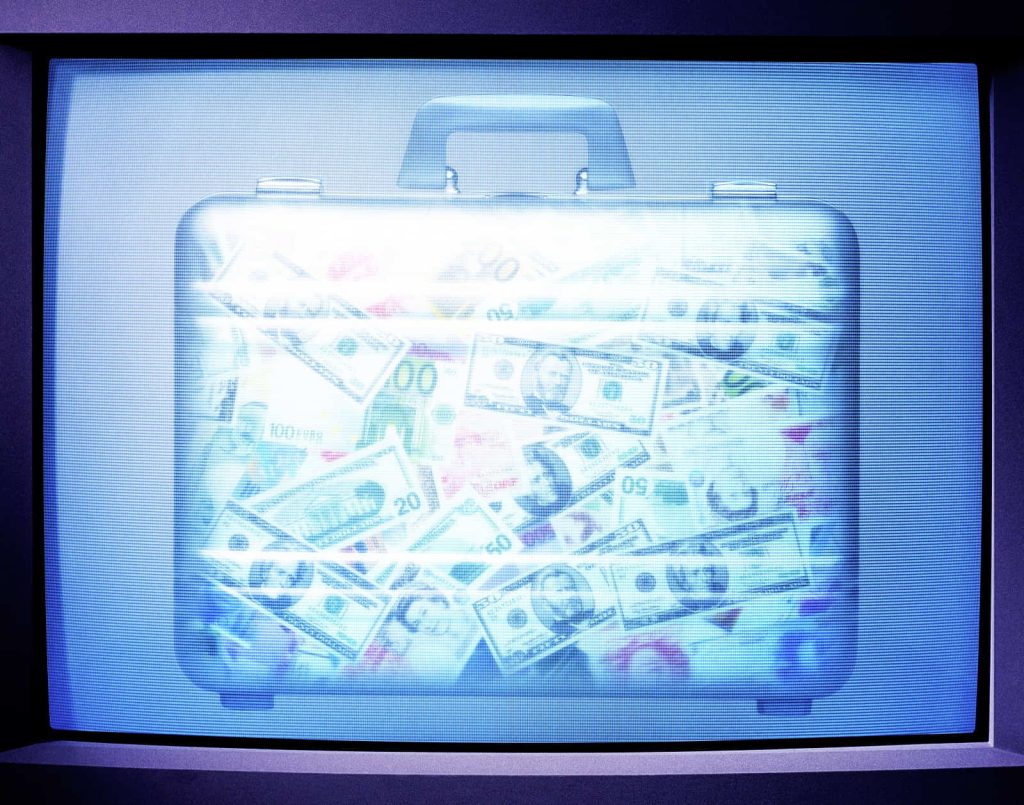

Let’s leave Bitcoin as a payments vehicle to one side. It has clearly found a substantial niche in catering for the payments requirements of drug gangs, smugglers, scammers, kidnappers, evaders of tax and capital controls, and money launderers – in short, it is the payments system of choice for the very substantial global illegal economy, replacing the cumbersome inefficiency of suitcases of banknotes. But for everyday transactions and transfers, Bitcoin doesn’t provide a useful payments function, either domestically or internationally.

The existing range of stablecoins doesn’t seem up to the task.

It has been suggested, including on The Interpreter, that stablecoins might provide the crypto-based payments solution. Stablecoins are digital currency with a fixed value against a conventional currency (usually the US dollar), in theory backed by conventional assets such as government securities.

The existing range of stablecoins doesn’t seem up to the task. Their value, in theory stable, is not assured. Terra and Luna lost most of their value, and even the largest stablecoin – Tether – has been fined for false statements about its backing. For those who are squeamish about their associations, stablecoins have the same potential for nefarious use as Bitcoin. Tether was the vehicle for a huge UK money-laundering scheme and its proponents laud its privacy and ability to avoid regulation.

As stablecoins currently bypass the requirements of know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering, the authorities will either have to give up on these requirements (which is unlikely) or enforce them on cyber-currencies, which would remove their main attraction of anonymity.

President Trump’s Genius Act may possibly address these issues, with regulations for combating money-laundering and other illicit activity. Stablecoins may be issued by institutions with unquestionable integrity: for example, JP Morgan plans to issue one.

If these issues are resolved, stablecoins might seem to have some advantages over the bank-based international payments system. The bank system is, indeed, very complicated. It involves multiple links: SWIFT intermediates a secure transfer message (it is not, itself, a payments system); the sending bank must have a trusted correspondent bank in the foreign country; then there is an exchange rate transaction, which will in turn require a two-way transaction via the US dollar to make the conversion using the deep US foreign-exchange markets and the Fedwire/CHIPS payments systems; and then the usual domestic payments infrastructure completes the transaction by shifting the money from the correspondent bank to the recipient’s bank. All this complexity has a cost. As the banks were, until recent years, the only way of making these transfers securely, there was a heavy monopoly levy as well. Big customers got better rates, but small transfers – workers’ remittances – paid exorbitantly.

Stablecoins could bypass some of this complexity. If the recipient had a wallet for the same stablecoin as the sender, stablecoins could be purchased and the transfer would be simple and secure. The hitch is that the recipient would still have to convert the stablecoin into local currency before they could make a purchase. Who will exchange a JP Morgan stablecoin for local currency (and what commission will they charge)?

Where crypto could potentially find a useful payments role is in the form of a central bank digital currency.

While the crypto promoters are trying to find an answer for this exchange problem, the bank-based system has taken note of the emerging alternatives. What do monopolists do when they are confronted by competition? They learn to compete. In recent years, commercial banks and other traditional payments systems have given far better exchange rates than formerly. For example, Wise will make a remittance transaction swiftly and with a favourable exchange rate, without going through any stablecoin links.

In short, stablecoins may have other uses (perhaps as a programable currency to facilitate commercial transactions), but are uncompetitive for international transfers.

Where crypto could potentially find a useful payments role is in the form of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). Central banks’ digital currency is already the key element in the domestic payments system. A CBDC could be used in international transactions to bypass both SWIFT and the need for a foreign correspondent bank. Some central banks are already experimenting with CBDCs to make international transfers to foreign central banks, but no central bank would allow its CBDCs to be held by the general public, as this would present a major threat to the stability of the conventional banking system.

America is, unsurprisingly, not rushing to support an innovation that might undermine the dollar’s global role. The Genius Act specifically prohibits the US Federal Reserve from developing a CBDC. Without a US CBDC, it is hard to see how a CBDC-based global payments system could rival the existing arrangements.